A Danish manager, Mette, made an agreement with her new team in Indonesia. The team had to deliver a new solution ready for today so she could present it to the customer tomorrow.

It’s been 14 days since Mette gave the task to the team and, at the same time, asked them if they would be able to manage it for today. They reported back to say that it could probably be done. She also urged them at the time to reach out if any problems arose. They didn’t do this.

Despite not getting back to Mette, the team has not delivered to the agreed deadline, and when she contacts them, it turns out that there’s still a long way to go! Mette is speechless. Why didn’t they say earlier that they couldn’t manage it?

…

Have you ever been in a situation where, like Mette, you’ve felt puzzled by the behaviour of global colleagues and thought something along the lines of: Why didn’t they say no if they meant no? Why didn’t they say that they couldn’t meet the agreed deadline? Why didn’t they just say it like it is???

The explanation is most likely that they actually did say this! They just said it in a different way than what you’re used to.

If you want to avoid ending up in these kinds of situations in the future, the first step is to become aware of how you and your global colleagues typically prefer to communicate.

And this is where you can use the terms ‘low-context cultures’ and ‘high-context cultures’, developed by cultural researcher Edward Hall.

In high-context cultures, much of the message lies not so much in the words that are said, but in everything else around them: the context.

The context is the situation in which the communication takes place, and it can be influenced by many different factors. We will take a closer look at them in a little while.

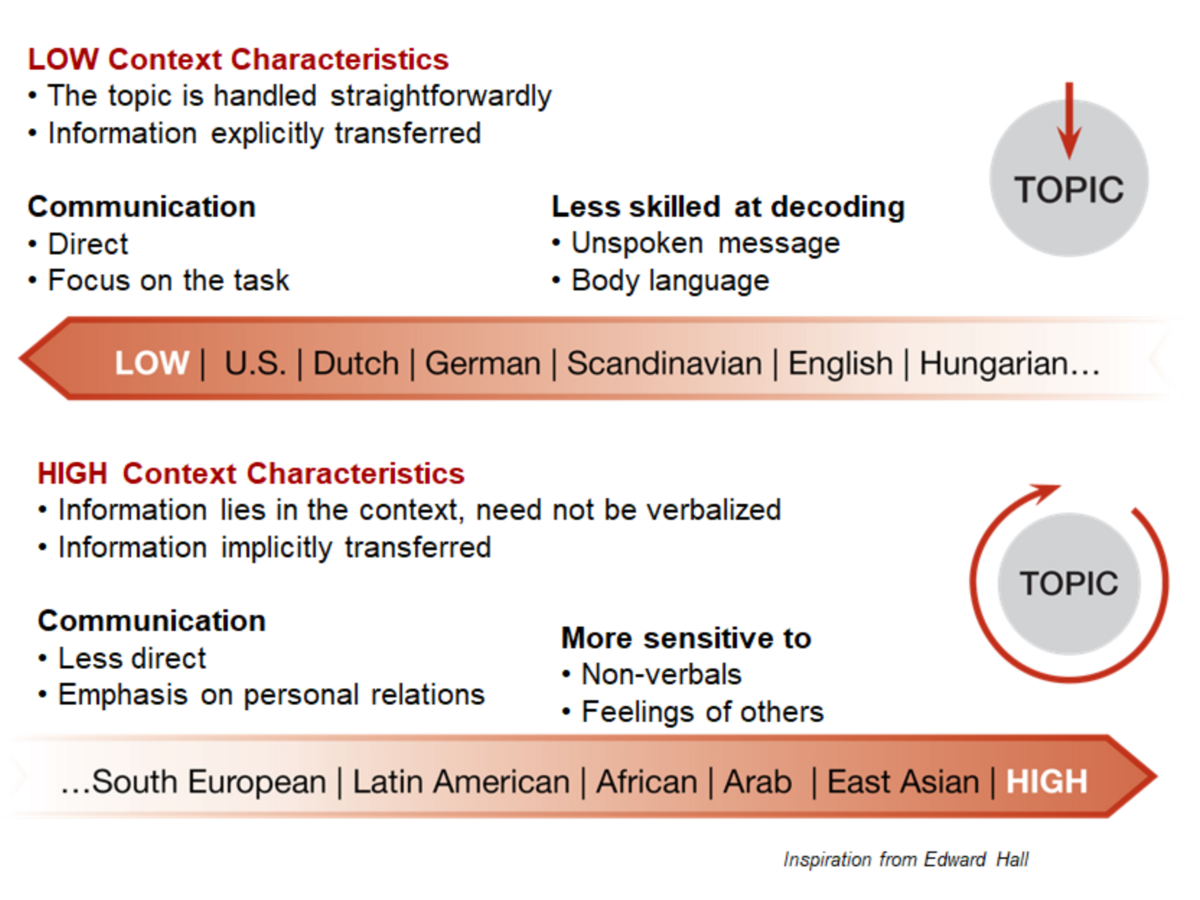

To start with, here’s a quick overview of the most important differences between low-context cultures and high-context cultures:

People from low-context culture backgrounds typically…

- prefer to communicate directly, explicitly and clearly;

- do not focus too much on the context of the communication;

- do not have much experience in decoding the context or ‘reading between the lines’; and

- focus on getting tasks done and put less energy into personal relationships.

People from high-context culture backgrounds typically…

- prefer to communicate in an indirect and nuanced way, with many layers in the communication;

- do not formulate ‘the actual message’ directly, but let it be implied from the context of the communication;

- excel at decoding the context and ‘reading between the lines’; and

- focus more on building and maintaining good personal relationships.

Now take a look at the picture at the top of this article. You can see – on the scale from low context to high context – where different national cultures are typically placed.

So, your American and Northern European colleagues will typically prefer low-context communication, while your colleagues from, e.g., East Asia, the Middle East and South America will typically prefer high-context communication.

We write typically – because it’s not ALWAYS like that.

As human beings, we all have a unique personality with unique experiences and a unique mix of cultural influences from our past. So, we can easily have personal preferences that differ from the mainstream in the society we live in.

Now take another look at the picture at the top of the article and try to place your own preferred way of communicating on the scale.

If you placed yourself at the low end of the scale, then read on! Because then you’ll get an insight into which factors can influence communication when you collaborate with high-context-communicating colleagues. You’ll also get three types of questions that can help you listen and read between the lines.

If you placed yourself at the high end of the scale, you can still carry on reading – and use this article to reflect on your own and your global colleagues’ preferred communication style!

What does ‘context’ cover?

In high-context cultures, context plays an important role in communication.

When decoding what a high-context-communicating colleague really means, be aware of the factors in the context that may affect his/her communication.

Here are the most important ones:

Language:

Although a large part of the message in high-context communication lies outside the spoken or written words, the language itself plays a role too. Words in languages spoken in high-context cultures can often have many different meanings – depending on the context in which the words are used.

And things get even more complicated if you and your global colleagues communicate in a language that is not your native language.

Nonverbal communication:

What’s the atmosphere like? Is there a lot of silence? Are there a lot of pauses in the conversation? What about body language, facial expressions and tone of voice?

Framework for communication:

Is it a formal setting, (e.g., a department meeting) or an informal setting (e.g., a coffee break)? What is the communication channel, e.g., email, chat, video conference or face-to-face meeting?

Personal relationships:

How well do you and your colleague know each other? Do you already have a strong personal relationship, and do you trust each other?

People present and hierarchy:

Is it a one-to-one meeting or are you in a large group? Who’s there? Your colleague’s manager or other people higher up the hierarchy? Are there other power dynamics at play (e.g., customer-supplier relationship)?

High risk or psychological safety:

Does your colleague perceive the situation to be ‘psychologically safe’, or is there a lot at stake? What is the risk to your colleague if he/she says something wrong or makes his/her boss, an important customer or others lose face?

If you come from a welfare society like the Danish one, bear in mind that many of your global colleagues will live in societies with a higher level of risk, where, for example, there would be enormous consequences for you and your family if you lost your job.

If Mette had listened and read between the lines…

Let’s return to the little scenario we described at the start of this article:

If the Danish manager, Mette, had read the article, she would have been aware that she is used to low-context communication, while her Indonesian team members probably prefer high-context communication.

She would have realized that she’d not yet managed to build a personal relationship with the people in her new team, and, as their boss, she’s ranked above them in the hierarchy at work. She would have been aware that these two factors make it unlikely for her team to give her a direct negative response such as: “A deadline of 14 days is completely impossible for us!”

When the team reported back that “it could probably be done”, the reservations implied in the word “probably” should have caused Mette’s alarm bells to ring.

And she certainly should NOT have interpreted the 14 days of silence from the team as “no news is good news”!

…

We’re not saying that it would have been easy for Mette. Because if you’ve been used to low-context communication all your life, it can be extremely challenging to decode what your high-context-communicating colleagues actually think.

But practice makes perfect!

Below you will find three types of questions that are good to ask in high-context cultures, as well as tips about the situations in which you would get the most out of asking the questions.

Because you can in fact help to influence the context of the communication. And if you create a safe context for your global colleagues, it will be much easier for you to decode their message.

3 types of questions to help you decode your global colleagues’ messages

1. How are you?

If you come from a low-context culture background, you might not put a lot of energy into building personal relationships with your colleagues. But if you collaborate with high-context-communicating colleagues, consider putting effort into this area.

In many high-context cultures, strong personal relationships are crucial to whether people trust each other – and this is also true in a professional capacity. And the more you and your colleague trust each other, the easier it will be for you to get the information you need.

So, remember to incorporate relationship-building questions, such as: “How are you?” into your collaboration!

The important thing is not exactly what you’re asking about, but that you remember to make room for small talk in your communication.

This applies when you meet physically, e.g., meetings and business dinners, as well as when you collaborate virtually.

For example, start your emails with a personal greeting along the lines of: “I hope you’re doing well?” Start your virtual meetings with a bit of small talk before you get on with the items on the agenda. And, if possible, use informal channels like chat and social media to ‘check in’ with your colleagues on a regular basis and to ask how things are going.

Sometimes we hear colleagues from low-context backgrounds complain that all that small talk is inefficient and a waste of time.

But the time you invest in personal relationships is typically time well spent!

And the gain is twofold:

On one hand, you create a more informal atmosphere for colleagues that makes it safer for them to say what they actually think, e.g., in a situation when you engage in small talk with them during a virtual meeting.

On the other hand, you continuously strengthen your relationship and mutual trust, which in turn makes it easier for your colleagues to talk more openly with you.

More examples of relationship-building questions:

- How are you feeling?

- How is your family?

- What did you do over the weekend?

- What’s the weather like where you are?

- How did you celebrate the X festival?

2. How can I help you get the job done by Friday?

One mistake that colleagues from low-context backgrounds often make in global collaboration is to ask closed questions that can be answered with either YES or NO.

If you’re used to low-context communication, you’re probably used to getting a no if the answer is no.

But if, for example, you ask your Chinese colleague if she can finish the task on Friday, you risk pushing her into a corner. Because even though she knows she can’t manage it by Friday, she will often find it both inappropriate and risky to reply with a direct answer such as: “NO – I can’t possibly manage that”.

This is especially true if you don’t know each other very well, and if a manager is present.

From your Chinese colleague’s perspective, such a direct response would appear confrontational, would risk damaging your relationship and may put you or her in a bad light in front of the manager. So instead, she answers: “YES – I can probably try to manage it by Friday,” and assumes you can decode the NO based on the context.

There are lots of situations in global collaboration where you need to get feedback and input from colleagues from a high-context background. Here’s what you need to do instead to get the information you need:

If you can, start by influencing the context so that it becomes as psychologically safe as possible for your colleague.

If possible, choose an informal setting such as a coffee break or a lunchtime, and remember to start with some relationship-building small talk. If you collaborate virtually, you can use chat or talk on the phone. Preferably, have the dialogue as a one-to-one or in a small group. Avoid the presence of your colleague’s manager or other superiors.

The safer your colleagues feel, the more likely they will be to say what they really mean.

If you don’t have the opportunity to influence the context, try looking at it from your colleague’s perspective. What factors in the context might affect how you interpret your colleague’s words? What’s the atmosphere like? Is it a formal or informal setting? What are the relationships and hierarchy like between those present? Etc.

Then ask open, exploratory questions that cannot be answered with a YES or NO.

So you should NOT ask, “Can you finish the job on Friday?”

Start instead with a question such as: “How can I help you finish the task by Friday?” (You can find more examples of open, exploratory questions at the bottom of this section.)

The open questions allow your colleague to put into words potential challenges without having to say a direct no.

Keep asking ‘around the topic’ until you’re sure you have the information you need. There’s no set formula for how many questions it takes – it depends on the context!

You might find it a little awkward to ask in this way. But it’s better to ask one question too many as opposed to too few questions. Think of the process like peeling off the layers of an onion. For every question you ask, you get closer to a complete answer.

When your colleague answers, make an effort to listen and read between the lines.

What words does your colleague use?

Pay particular attention to so-called ‘softeners’, which soften the message – these can be formulations such as:

- We will try to achieve that…

- Hopefully we can solve it…

- Yes, yes – we can do that, but it will be a bit difficult…

You should see these formulations as warning signs, as they will often indicate that there’s a problem.

Also bear in mind which factors in the context may affect how you interpret your colleague’s words (formal/informal, relationships, one-to-one/larger group, hierarchy, high risk/psychological safety).

And observe body language, atmosphere, pauses and things that are not being said.

If you work together virtually and you’re wondering why you’ve not heard from your colleague for a while, then make the first move – preferably by picking up the phone, where through open, exploratory questions you become wiser about the situation.

More examples of open, exploratory questions:

- What does your calendar look like next week?

- What’s your next step?

- What questions do you have at this point?

- What will you do to reach the deadline?

- How did you manage to fix it?

3. Could you please run through the new instructions for me?

Let’s say you’re responsible for training a group of Indian colleagues on a new task. After one of the training sessions, when you ask if there are any questions, you’re greeted with silence from the whole group.

If you come from a low-context background, you may conclude that everyone is up-to-speed and that you can confidently continue with the training.

But you can’t be too sure. There may well be things that some of your Indian colleagues have not grasped. But perhaps they dare not risk asking a ‘wrong’ question in front of the whole group and losing face – or damaging the relationship with you by suggesting that you have not explained things well enough.

In situations like these – that is, when you’re in charge of training, educating or transferring knowledge to global colleagues – you can greatly benefit from asking recap questions such as: “Could you please run through the new instructions for me?” (See more examples of recap questions at the bottom of this section.)

Again: If you have the opportunity to influence the context so that you create a psychologically safe environment for your colleagues, then do it: If possible, talk one-to-one or in a small group, choose an informal setting (e.g., a break), and make sure no superiors are present.

Be extra aware if you or your global colleagues communicate in languages other than your native language. It can be a source of misunderstanding and make it even less safe for high-context-communicating colleagues to ask questions in front of a larger group.

More examples of recap questions:

- Could you please repeat the most important points from the meeting?

- Could you please summarize our agreement?

- Just so we completely agree on what we do from here: Will you go through the process for me again?

- The office in Copenhagen wants everything in writing. Could you please send me an email outlining our agreement in just ten lines so that we satisfy them?

A few concluding remarks

Culture-related misunderstandings can create a lot of frustration.

At C3 Consulting, we’ve experienced that low-context colleagues can interpret the behaviour of high-context colleagues as reserved, unreliable, vague, dishonest or unprofessional.

And we have seen high-context colleagues describe the behaviour of low-context colleagues as aggressive, inappropriate, condescending, rude or unprofessional.

But we also see that when people are first introduced to the typical differences between low-context cultures and high-context cultures, it’s a real Aha! moment:

So, we’re basically just used to communicating in different ways?? We had no idea!

So, remember when communicating with colleagues around the world:

- Become aware of how you and your global colleague typically prefer to communicate. Explore where each of you is placed on the ‘context scale’ with low context at one end and high context at the other. And remember, this is just a scale and not either-or. The important thing is how you are relatively positioned in relation to each other.

- Bear in mind that although national culture influences our communication preferences, your colleague may have completely different personal preferences compared to what is typical of that culture. Always look at the person as a whole.

- Recognize that you probably want to communicate politely and professionally with your colleague – as does your global colleague. But perhaps it’s expressed in different ways. And remember that it’s not about right or wrong – but about different approaches.

The questions we’ve suggested that you ask your high-context-communicating colleague are a good place to start when learning to listen and read between the lines.

If you want a more detailed guide, then we recommend our book ‘Global Perspectives’, where we spend an entire chapter on high- and low-context communication. Read more about the book here.

You can also use our 4R Model to help you to decode and influence the context yourself. Read more about it here and here.

Where to go from here

Can we help you or your company boost your communication across borders and cultures? See our cultural understanding and global mindset training here or contact us for a chat.

Want more inspiration for your cross-cultural work? Follow us on LinkedIn – and sign up for our newsletter using the form below.